CHAPTER/EPISODE TIMELINE SO FAR

THE MOST OBSCURE PLEASURE: CAPTAIN COOK TO WORLD WAR 2

Neither are they strangers to the soothing effects produced by particular sorts of motion; which, in some cases, seem to allay any perturbation of mind, with as much success as music. Of this, I met with a remarkable instance. For on walking one day about Matavai Point, where our tents were erected, I saw a man paddling in a small canoe so quickly, and looking about with such eagerness, on each side, as to command all my attention. At first, I imagined that he had stolen something from one of the ships, and was pursued; but on waiting patiently, saw him repeat his amusement.

He went out from the shore, till he was near the place where the swell begins to take its rise; and watching its first motion very attentively, paddled before it, with great quickness, till he found that it overtook him, and had acquired sufficient force to carry his canoe before it, without passing underneath. He then sat motionless, and was carried along at the same swift rate as the wave, till it landed him upon the beach. Then he started out, emptied his canoe, and went in search of another swell. I could not help concluding that this man felt the most supreme pleasure, while he was driven on so fast and so smoothly, by the sea.

William Anderson, Matavai Bay, August 1777.

One of the most eloquent things ever said about surfing was said by a British surgeon observing Tahitians riding waves in 1777: “I could not help concluding that this man felt the most supreme pleasure while he was driven so fast and so smoothly by the sea.”

Yep.

From there, surfing was an obscurity, practiced by dusky heathens far out in the South Pacific - despite the efforts of 19th Century Pesky Puritans and Christian Killjoys to put the kibosh on the surfing, and hula, and the Hawaiian language. Idiots.

This episode features Robert Bonine’s “actuarial” movies of surfers at Canoes, Waikiki in 1906 - shot for Thomas Edison. Hawaiian tourism began to flourish around then, and the visitor’s board and hotels used images of surfing to lure visitors from the mainland and all over to Hawaii - at the time the most remote inhabited place on earth. This episode uses footage from the Trunk It project created for the Surfing Heritage and Cultural Center by Ben Marcus, which has images of surfing, hula, canoe racing, beach boys and Hawaiian life through the first half of the 20th Century and right up to World War 2.

This episode ends with a color movie of the First National Surfing and Paddleboarding Championship at Long Beach in 1938. There’s a surprising number of surfers in the water. And on the horizon in the background, the Pacific Fleet: which soon after was moved to Oahu despite objections by an admiral who felt the fleet would be unprotected.

The admiral was sacked, the fleet was bombed, the War in the Pacific began and millions of Americans got a free ride through the Hawaiian islands.

Those who survived - surfed.

2. LIFE AFTER WARTIME/THE GOLDEN YEARS/FROM HERE TO GIDGET: 1945 - 1959

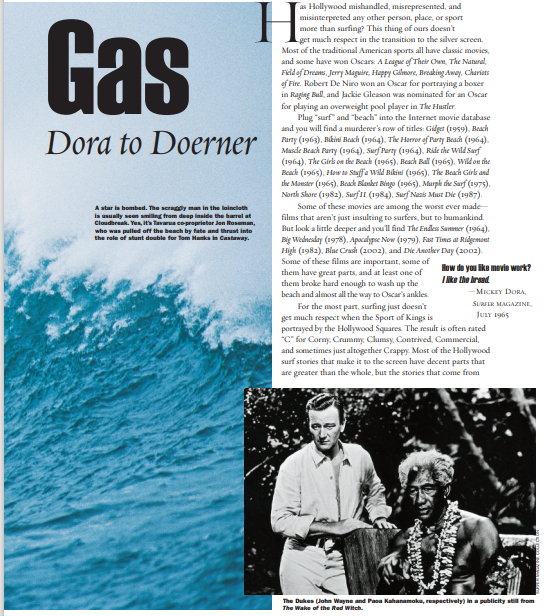

This episode picks up with that 1938 Long Beach surf contest and moves with the Pacific Fleet to Hawaii. There is a brief scene in From Here to Eternity where two Army guys talk about surfing, and then the attack on Pearl Harbor brings millions of service people through Hawaii to train and support the War in the Pacific. Bruce Brown, Walter Hoffman, Hobie Alter, Duke Kahanamoku and Tom Blake were among the well-known surfers who served in the military during World War 2.

This episode uses moving images of Outrigger Canoe Club paddleboarding and canoe races during World War 2 and also the Sweet Sixteen footage by John Larronde showing California surfers on huge, heavy hardwood boards surfing straight lines at San Onofre, Malibu, Rincon and Ventura Overhead in 1947.

That year, 1947, was a turning point in surfboard design where surfing innovators like Bob Simmons, Matt Kivlin, Joe Quigg and others used wartime technology in planing hull design and plastics to make surfboards lighter, shorter, faster and more maneuverable. There is footage from the early 1950s showing surfers riding Malibu Chip surfboards: no more straight off, Adolf, These surfers are fading, turning, doing cutbacks and all of a sudden looking modern

Rincon in 1947. No one outside, and only three guys in the middle. Joe Quigg is one of them, struggling on big equipment and thinking there must be a better way.

Surfing shows up in random places through World War 2 - like the Merry Melodies cartoon spoof Malibu Beach Party (1943) - and after, then in 1953, Bud Browne (1912 - 2008) = who served in the Navy teaching Marines to swim - made the first “four wall” surf movie: Hawaiian Surfing Movie, which he premiered at John Adams Junior High in Santa Monica to 500 people.

Browne knew he’d stepped into something lucrative and fun which used his swimming and creative skills. Browne was joined by other surfers who picked up cameras and filmed their surf trips: In 1955, Bud Browne released Hawaiian Surfing Movie, followed by Trek to Makaha in 1956 and The Big Surf in 1957, capturing the growing excitement of surfing in Hawaii. That same year, Greg Noll made Search for Surf, showcasing his adventurous surf expeditions. In 1958, Bruce Brown debuted Slippery When Wet, while John Severson released Surf, further expanding the audience for surf films on the mainland. By 1959, Browne had made Cat on a Hot Foam Board, Bruce Brown followed with Surf Crazy, and Severson produced Surf Safari, marking the end of the decade with a burst of creativity that helped establish surf cinema as a distinct genre.

Surfing was more popular than ever in the 1950s, but still a somewhat obscure deal in an America that was a new superpower with a booming economy and two chickens in every pot.

When the squares finally noticed surfing, they shrugged it off as just another fad, lumping surfers in with beatniks, beach bums, artists, homosexuals, Communists and anyone who lived outside the lines. But for Miki Dora and the wave riders of the 1950s, those years were pure magic—the Golden Age of surfing. Beaches were wide open, the waves perfect and unspoiled, and the surfboards were evolving into sleek, beautiful instruments of motion. Cruising along the sand in a gleaming Bel Air, a wood-paneled Woodie, or a rumbling Ford panel van, the salty breeze in your hair, the air carried the intoxicating melodies of Patsy Cline, Little Richard, Elvis Presley, Miles Davis, Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, and the Everly Brothers. Each chord, each riff, each soaring vocal felt like sunlight on your skin, like the perfect curl of a wave waiting just for you—a soundtrack to a world where freedom, style, and the ocean ruled.

In the late 1950s, a Lebanese musician named Richard Mansour performed as Dick Dale and the Rhythm Wranglers, but when Dale wanted to catch the “pulsification” of waves and surfing, he changed the name of his band to Dick Dale and the Del Tones. In 1958, Dick Dale recorded “Let’s Go Trippin’”, a fast, reverb-soaked instrumental that would become the first surf rock hit. Dale and the Del Tones began performing at Surfer Stomps which lit up Southern California’s beach towns, with the Balboa Pavilion Ballroom in Newport Beach as the epicenter of the craze. Teens and surfers packed the dance floor, the air buzzing with excitement as Dick Dale and other early surf bands blasted reverb-heavy guitars and driving rhythms. The vibe was electric and carefree—palm trees swaying outside, ocean breezes drifting in, girls in poodle skirts and boys in slicked-back hair twisting and stomping to the beat, celebrating the freedom of the waves and the golden, sun-soaked surf culture that was just beginning to explode.

The 1950s were the Golden Years, and then Along Came Gidget (1959).

WAXPLOITATION: GIDGET, BLUE HAWAII, RIDE THE WILD SURF, BEACH PARTY 1959 - 1964

In 1959, Columbia Pictures had a major hit with Gidget, the first Hollywood “Waxploitation” movie featuring non surfers portraying surfers in scripted stories. Gidget looked back on the Golden Years of the 1950s and began to end them, lighting the fuse of surf culture that would blow up out of the late 1950s into the early 1960s.

Kathy Kohner’s father, Frederick “Fred” Kohner, was a Hollywood screenwriter and novelist who drew inspiration for his 1957 novella Gidget: The Little Girl with Big Ideas from his teenage daughter’s surfing adventures along the sun-soaked shores of Malibu. Kathy, nicknamed “Gidget” (a blend of “girl” and “midget”), was a petite, fearless teen who rode waves alongside boys, chased first crushes, and navigated the male-dominated beach culture, and her exploits became the heart of a story that captured the imagination of a generation.

Published by Putnam in 1957, Fred Kohner’s novella sold over 500,000 copies and was translated into Japanese, Spanish, and Hebrew, becoming a commercial sensation that introduced mainstream readers to surf culture and teen romance. While it didn’t earn the literary acclaim of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, Gidget resonated with young audiences eager for sun, sand, and freedom.

THE FACT AND FICTION - REALITY AND FANTASY - OF GIDGET

The book was quickly adapted into a 1959 Columbia Pictures film starring Sandra Dee as Gidget, with James Darren as Moondoggie, Cliff Robertson as the Great Kahoona and Cloris Leachman, Arthur O’Connell, and John Crawford in supporting roles. Made for roughly US $750,000 (about $8.3 million today), the film earned $1.5 million in U.S./Canada rentals (around $16.5 million today), cementing the image of the “surf teen” and launching a wave of sequels, TV adaptations, and spin-offs that defined 1960s youth culture.

If remade today with comparable star power, the cast could bring the classic surf adventure to life with contemporary star power. Zendaya would embody Gidget herself, the spirited, adventurous teen who rides waves and navigates beachside romance with charm and confidence, while Timothée Chalamet would play Moondoggie, the cool, swoon-worthy surfer and ideal teen heartthrob. The wise, surf-savvy mentor figure of the Big Kahuna could be portrayed by Oscar Isaac, bringing charisma and authority to the role, while Gidget’s parents—her father Russ Lawrence and mother Anne Lawrence—could be played by Jeff Bridges and Rachel McAdams (or Jennifer Garner), offering warmth, humor, and the grounding presence of family. Adding depth and energy, Rachel Zegler could play Gidget’s younger sister or cousin, full of youthful exuberance, and Awkwafina could provide comic-relief as a fearless, witty sidekick. A supporting ensemble of rising young stars like Asher Angel, Isabela Merced, Noah Jupe, and Lana Condor would capture the camaraderie and carefree spirit of Southern California surf culture, with veteran actors such as Sam Elliott, John C. Reilly, or Bill Murray appearing in cameo roles as eccentric local surfers or shopkeepers, honoring the history of the scene while bridging past and present.

Gidget lit the fuse and there were increasingly louder and more resonant explosions of surf culture: Gidget lit the fuse and there were increasingly louder and more resonant explosions of surf culture: In 1961, Elvis Presley portrayed a surf-stoked kamaaina Hawaiian kid wearing striped M Nii trunks, home from the service singing Can’t Help Falling in Love to his grandmother in Blue Hawaii. That was followed by the first two American International Frankie and Annette movies - Beach Party (1963) and Muscle Beach Party (1964).

Ride the Wild Surf (1964) starred Tab Hunter as Jody Wallis, Fabian Forte as Tony Matteo, Peter Brown as Greg, Susan Hart as Kathy, Lynne Weber as Lorrie, Chris Noel as Carolyn, and James Mitchum in a supporting role, while the breathtaking surf sequences were performed by legendary surfers of the era, including Greg Noll, Miki Dora, and other top wave riders, lending authenticity and daring athleticism to the Hollywood depiction of big-wave surfing.

FOUR NON BLONDES: JAMES DARREN, FABIAN FORTE, ELVIS PRESLEY, FRANKIE AVALON

Interestingly, many of the actors who became icons of surf culture on screen were not originally of the beach: Frankie Avalon, Fabian, and James Darren all hailed from South Philadelphia, and even Elvis Presley, who starred in Blue Hawaii, was from Tupelo, Mississippi, yet each convincingly played sun-soaked, wave-riding surfers and beach idols in Hollywood films.

George Lucas’ nostalgic American Graffiti (1973) is set in 1962. In one scene, the hotrodder Milner snaps off the radio when the Beach Boys Surfin’ Safari comes on.

Carol - played by Mackenzie Phillips - is a Gidget-aged girl in a Dewey Weber t-shirt who protests:

Carol [John turns off the radio]

Why did you do that?

John Milner

I don't like that surfin' shit. Rock and roll's been going down hill ever since Buddy Holly died.

Carol

Don't you think the Beach Boys are boss?

John Milner

You would, you grungy little twirp.

Carol

Grungy? You big weenie! If I had a boyfriend, he'd pound you.

John Milner

Yeah, sure.

A hot-rodding greaser from California’s Central Valley wouldn’t like surf music, but a good chunk of America and the rest of the world thought the Beach Boys and all of it was boss. Surf music roared out of the 1950s into the 1960s with chart‑topping surf songs amplifying the sound of the new California lifestyle: Dick Dale’s “Let’s Go Trippin’” (1958) and The Ventures’ “Walk, Don’t Run” (1960) to Jan and Dean’s “Surf City” (1963), The Beach Boys’ “Surfin’ Safari” (1962), The Chantays’ “Pipeline” (1963), The Surfaris’ “Wipe Out” (1963), and The Marketts’ “Out of Limits” (1964).

The surf explosion lit by Gidget brought hundred and thousands of hodads, wannabes and thrill seekers from the shady turf to the sunny surf. Guys like Miki Dora, Greg Noll, Jack O’Neill, Hobie Alter and many other surftrepeneurs sold surfboards, wetsuits, clothes and packed auditoriums for four wall surf movies - making money with one fist while shaking the other fist at the hoardes of hodads cluttering their once-empty lineups and happy hunting grounds - places spelled out in no uncertain terms in Surfin’ Safari.

At Huntington and Malibu, they're shootin' the pier

At Rincon, they're walkin' the nose

We're goin' on safari to the islands this year

So if you're comin', get ready to go

They're anglin' in Laguna in Cerro Azul

They're kickin' out in Doheny too

I tell you surfing's mighty wild, it's gettin' bigger every day

From Hawaii to the shores of Peru

The Happy Few surfers who had enjoyed the Golden Years of the 1950s were appalled by the treatment of surfing by Hollywood “Waxploitation” movies and surf music. And at some point, Bruce Brown had had enough and made a surf documentary with a message in.

4. REAL SURFERS DON’T BREAK INTO SONGS IN FRONT OF THEIR GIRLFRIENDS!: ENDLESS SUMMER 1964

Perfect wave DNA. Cape Saint Francis to Surf Ranch.

Bruce Brown was born on December 1, 1937, in San Francisco and grew up in Long Beach, California. He took up surfing in the early 1950s, and during a stint in the U.S. Navy in Hawaii, he began filming surfers with an 8‑mm movie camera. After his discharge, Brown showcased his home-movie surf footage in small venues, charging local audiences for screenings, and quickly transitioned into making full-length surf films.

His first major surf feature, Slippery When Wet (1958), was shot in Hawaii, particularly the North Shore of Oahu during the winter of 1958. He raised about $5,000 for the project, largely with support from surfboard manufacturer Dale Velzy, and used a 16‑mm camera to capture the waves.

That $5000 in modern money is the equivalent of about 2025$55,000 and it was on that shoot, Brown named a North Shore spot “Velzyland” as a tribute to Dale Velzy, just as Captain Cook ahd named the island the Sandwich Islands in honor of his sponsor.

Following that, Brown released Surf Crazy (1959), continuing his exploration of Hawaiian surf spots. In Barefoot Adventure (1960), he traveled to California and Hawaii, filming a mixture of competitive and casual surfing. Surfing Hollow Days (1961) included footage from Pipeline, Oahu, showcasing more extreme waves, and Water‑Logged (1962) compiled highlights from previous films while helping Brown raise funds for his next, more ambitious project. Across these films, Brown’s shooting typically took place in the fall and winter, with editing completed in the spring to prepare for summer screenings, and his equipment remained light and portable—often under 100 pounds of cameras, mounts, and sound gear.

All of this groundwork culminated in The Endless Summer, which Brown began planning in the early 1960s. He and his small crew traveled around the world for roughly two years, filming in Australia, Ghana, South Africa, New Zealand, Senegal, Tahiti, and Hawaii. For this film, Brown financed the roughly $50,000 budget himself, using modest 16‑mm cameras and minimal gear, navigating challenging surf conditions, remote locations, and unpredictable weather. The film had a limited premiere around 1964 and a wide release in 1966, ultimately grossing between $20 million and $30 million worldwide, an extraordinary return on a relatively tiny budget.

Brown cringed at the Hollywood Waxploitation movies and the silent screm of Endless Summer was:

“REAL SURFERS DON’T BREAK INTO SONG IN FRONT OF THEIR GIRLFRIENDS!!!!!”

Bruce Brown made The Endless Summer to foul off Eric von Zipper’s assertion: “These bums is bums” as he showed Mike Hynson and Robert August wearing suits and ties to board a jet at LAX, and that far from bums, they were surfisticated travelers, adventurers and athletes.

Bruce Brown himself was the blonde, unthreatening, honest, healthy boy-next-door interface between the surfing world and civilians - the perfect guy to introduce squares to the Secrets of the Sea. His narration was honed by many live shows before he laid it down permanently.

The Endless Summer was a beautifully thought out and crafted documentary and an enormous success. It holds up to modern viewers like Lawrence of Arabia or 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Matt Warshaw summed it up nicely nicely in The Encyclopedia of Surfing:

“Editing his film in early 1964, Brown masterfully split the difference between his core surfing audience and a hoped-for mainstream audience. Endless Summer had far less actual wave-riding than any surf film yet produced, and Brown, while never once sounding pedantic to surfers, narrates the movie as a primer to nonsurfers. His definitively casual Southern California voice is in fact the star of the film—more so than the seen-but-not-heard August and Hynson—and imitation Brown voice-overs would be the norm in surf movies for the next 30 years. (The Sandals' soundtrack is another enduring Endless Summer legacy, along with the John Van Hamersveld-designed poster, featuring Brown, August, and Hynson in silhouette against a Day-Glo orange, pink, and yellow background.)

Many of the era's best surfers made cameo appearances in Endless Summer, including Phil Edwards, Butch Van Artsdalen, Greg Noll, Nat Young, George Greenough, Paul Strauch, Lance Carson, and Mickey Dora.

Brown toured a 16-millimeter version of Endless Summer across the East and West coasts in 1964; the following year he screen-tested the movie at the Sunset Theater in Wichita, Kansas, in the dead of winter, and it was a smash hit; in 1966 the film was re-edited slightly, blown up to 35-millimeter, and put into general release by Columbia Pictures, where it eventually earned $30 million. The critics went into raptures. Time magazine called Brown a "Bergman of the boards," and his movie was "an ode to sun, sand, skin and surf." Newsweek named Endless Summer as one the 10 best films of 1966. (Robert August, who went on to become a successful board manufacturer, later said that Endless Summer was a hit in large part because it served as "a big time-out" from the Vietnam War.) In 1967, at the height of the Cold War, the US State Department sponsored Endless Summer's entry to the Moscow Film Festival.”

And if you’re crunching the numbers, The Endless Summer was made on a modest budget of roughly 1964$50,000 —about $540,000 in 2025 dollars—yet it went on to gross between $20 million and $30 million, equivalent to 2025$200–$300 million today, making it the most successful documentary of its era. Bruce Brown’s small investment turned into a monumental success, establishing the film as both a financial triumph and a defining work of surf cinema.

The Cape Saint Francis sequence of Endless Summer has a long backstory, but it launched the idea of the search for the perfect wave - which continues to this day with recent discoveries at Skeleton Bay in Namibia and all the way north to Norway.

ANDY MAKES A MOVIE: SAN DIEGO SURF 1969

It’s not a homoerotic surf movie; it’s a surf-erotic homo movie. Honestly, as I recall, it was like Buster Keaton ate acid and had Abercrombie dudes double as the Pump House Gang. It’s a dilettante delusion, man.”

Chris Malloy on San Diego Surf

In 1969, AIndy Warhol went west to La Jolla to make a surf movie - possibly inspired by The Pump House Gang - called San Diego Surf. I knew a couple of people who’d seen the movie, but it required a pilgrimage to the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Randy Hild and friends made that pilgrimage because they wanted to show the movie during the Quiksilver Pro New York in September of 2011.

But Randy and friends saw it, said there were two many Golden Showers and other inappropriate misappropriations and they kiboshed.

However, there is a black and white DVD called Andy Makes a Movie that shows Andy shooting the movie from Cliff Robertson’s house in La Jolla, as he is chased around by a pesky journalist asking pesky questions.

They were shooting late May and then Andy went back to New York where he was shot by a crazed devotee in the first week of June. The movie was put in the shelf and not edited together until many years later.

Chris Malloy had also seen San Diego Surf and thought he had a VHS copy of it. He couldn’t find that VHS but when he heard the movie described as “a homoerotic surf movie” he scoffed and said: “…not a homoerotic surf movie; it’s a surf-erotic homo movie. Honestly, as I recall, it was like Buster Keaton ate acid and had Abercrombie dudes double as the Pump House Gang. It’s a dilettante delusion, man.”

A weird sidebar to surf movie history, maybe worth an entire episode, maybe not.

We could talk to Randy Hild, Chris Malloy and maybe Jon Roseman, whose family house was next door to Cliff Robertsons.'

And if not that, then how about?

OR HOW ABOUT BATMANDY: The surf-cultural misappropiation of Batman (1967), San Diego Surf (1969), The Brady Bunch (1972), Hawaii Five-O (1974)

Okay Andy Warhol making a surf-erotic homo movie - a dilettante delusion - could be a standalone episode, but then I remembered the Surf’s Up, Joker’s Under episode of Batman which was camp with a Capital C: Batman pulling out a can of shark repellant from his Batbelt and fending off a toothy critter - and beating Joker by pulling off spinners.

There’s some snappy back and forth between Batman and Joker as they prepare to square off at Rat Beach in Torrance:

BATMAN

Well? Into the soup?

JOKER

Why not? It’s a shorebreak surf. Not too long a paddle to the peak!

When I showed this to Herbie Fletcher many years ago and asked if he did the stunts he said: “Wow is that real? I thought that was an acid flashback!!” Could be good to interview him again.

So Surf’s Up! Joker’s Under! to San Diego Surf would swing from Goofy to Gay. Hoakey to Homoerotic, Campy to Cultish - Bruce Wayne to Andy Warhol - but then I thought: What other shows in the late 1960s also usurped the surfing thing for an episode?

I remembered a surf-adjacent episode of Hawaii Five Oh with some Point Break-class corny dialgoue. Turns out it was The Banzai Pipeline (1974) practicing some surf cultural misappropriation.

Somer surfers get mixed up with murderous bad guys on Oahu. At the end, one guy shooting the curl at Pipe and one guy shooting the guy shooting the curl at Pipe with a 16 mm camera get shot by a sniper.

DANNO

Patch me through to McGarrett.

McGARRETT (on the radio)

Yeah Danno.

DANNO

Steve? The guy is not here.

McGARRETT

There’s only two places a surfer would be on a day like this.

DANNO

Sunset Beach?

McGARRETT

Yeah and the Banzai. Meet me at the Pipe.

So Batman and Andy Warhol and Danno and McGarrett. Pretty good surf-cultural misappropriation.

Any thing else?

Of course! Greg Brady face-planting a coral head at Publics because he wore the tiki amulet.

Haole die!

According to Chat GPT, that really was the actor face-planting onto a coral head at Publics - a place that really is shallow and gnarly.

Yes — that story is true.

During the filming of The Brady Bunch episode “Hawaii Bound” (Season 4, Episode 1, aired September 22, 1972), Barry Williams, who played Greg Brady, was actually injured while surfing in Hawaii.

Here’s what happened:

While shooting a surfing sequence near Waikīkī, Williams tried to catch a real wave instead of sticking to the calmer waters arranged for filming. He wiped out and struck his face on a coral head, suffering cuts on his forehead and nose. The injuries were real, and the swelling and scabbing you can see in the finished episode weren’t makeup — the production just kept shooting.

In his memoir Growing Up Brady: I Was a Teenage Greg (1992), Williams confirmed the incident, joking that the coral “won” and that the crew decided to work the injury into the scene continuity rather than halt production.

So there’s probably more misappropriation from that 60s into 70s era, but Batman x Andy Warhol x The Brady Bunch x Hawaii Five-Oh might be enough: Corny, cultish, coral and cutbacks.

REVOLUTION, REVOLTS, EVOLUTIONS: THE HOT GENERATON, FREE AND EASY, EVOLUTION, FANTASTIC PLASTIC MACHINE 1964 - 1969

These are the movies made on the cusp and either side of the Shortboard Revolution in 1967, when Nat Young won the World Title at Ocean Beach, San Diego, doing Total Involvement surfing on Magic Sam.

According to Chat GPT: From 1964, Ride the Wild Surf brought big‑wave drama to Hollywood audiences. 1966 saw Bruce Brown’s groundbreaking documentary The Endless Summer, capturing surfers chasing perfect waves worldwide. In 1967, Paul Witzig’s The Hot Generation explored the emergence of shortboard surfing, followed by creative surf films like Free & Easy in 1968. By 1969, innovations in style and board technology were documented in Witzig’s Evolution and the visually striking The Fantastic Plastic Machine.

There are probably others from this era. But this episode is all about the Shortboard Revolution.

CALIFORNIA’S DONE, WE’RE ON THE RUN: PACIFIC VIBRATIONS AND INNERMOST LIMITS OF PURE FUN 1969 - 1974

Beaulieu - the Cadillac of Super 8 cameras.

THE SUPER8ERS: WILLS, SPAULDING 1968 - 1980

The Super 8 era of surf filmmaking, roughly from 1968 through the early 1980s, was a golden age of underground creativity when surfers became their own documentarians. The cameras were cheap, light, and easy to carry down the beach, giving rise to a new kind of handmade surf cinema—grainy, sun-bleached, and deeply personal. These films weren’t studio projects or commercial releases; they were passion projects made by surfers for surfers, screened in garages, surf shops, and makeshift beach theaters with the hum of a projector and the smell of salt still in the air.

One of the earliest innovators was George Greenough, who used modified Super 8 housings to shoot from inside the barrel for The Innermost Limits of Pure Fun (1970). Around the same time in Australia, Chris Bystrom was filming his own Super 8 reels of the emerging shortboard revolution, sequences that would evolve into his later 16 mm features like A Winter’s Tale.

Dn Balch said: “Very interesting content there. Obviously, a lot of material and content to deal with. Love the old 1947 Rincon shots! About the Super 8 era, Back in 1971 , Wardy Ward showed me how he and George Greenough built water housings for movie cameras so I built my own and made a super 8 film called “Sweet Natural Juice” later renamed “Fluid Pleasures”. I showed it four times in 1972 into ‘73. It sold out in Santa Barbara, Pismo Beach, Monterey and Santa Cruz.

It inspired Greg Huglin, Chris Klopf and Steve Spaulding to make their own early films that definitely advanced the whole genre with better equipment and more locations. Mine was Santa Barbara, Hawaii and France, early on. Some of my early footage has been used in other recent modern films by some great film makers and it always is so rewarding to me. I could have never imagined it back then!”

By the mid-1970s, the movement had gathered momentum in California. Steve Spaulding made Scream of the Surf (1974) and later captured remote waves in Bali High (1981), one of his most celebrated Super 8 films, which showcased unspoiled breaks in Bali, Java, and Nias. Around the same time, Greg Weaver and Spyder Wills released Stylemasters (1978), an underground classic that celebrated post-longboard expression and stylish, progressive surfing. Bill Delaney, before creating his 16 mm masterpiece Free Ride (1977), also experimented with Super 8 to refine his camera angles and pacing.

In Australia, Jack McCoy was cutting his teeth on Super 8 reels in the late 1970s before moving to 16 mm for films like Bunyip Dreaming and Green Iguana, and filmmakers such as Duncan Campbell were creating collective projects like Australian Summer (1979), which paired Byron Bay’s bohemian surf culture with music and art. Scott Dittrich’s later Fluid Drive (1981) is often considered one of the last great Super 8 surf films—lyrical, meditative, and closing out the format’s reign just as VHS began to take over. NOT SURE IF THAT IS ACCURATE ABOUT FLUID DRIVE?

The Super 8 era gave surf cinema its soul. It was intimate, experimental, and authentic—a time when surfers made films not to impress Hollywood, but to capture the feeling of living inside the dream. Its influence would ripple through the VHS explosion of the 1980s and into the DIY aesthetics of modern surf filmmaking today.

THE TOPANGLE: Rohloff, Jepsen, Dittrich (1960s - 1980s, but mostly 70s)

BUSTING DOWN THE DOOR: FREE RIDE (1977)

The 21st Century documentary Bustin' Down the Door (2008) looks back on a pivotal and turbulent era in surfing history: the mid‑1970s, roughly 1974‑1976, when a wave of determined Australian and South African surfers descended on Hawaii’s North Shore and permanently changed the sport. These surfers — including Shaun Tomson, Wayne ‘Rabbit’ Bartholomew, Mark Richards, Ian Cairns and Peter Townend — arrived with new boards, new ambition, and a fierce competitive edge that challenged Hawaii’s surfing traditions.

During that era, several surf films captured the energy, locations and style‑shifts of this “assault”. These include: Morning of the Earth (1972) — directed by Alby Falzon & David Elfick (Australia/Bali/Hawaii). Crystal Voyager (1973) — directed by David Elfick & starring George Greenough (Australia/California).

Tubular Swells (1976) — via SurfResearch list covering Bali/Australia/Hawaii surfing by Aussies & South Africans

A Matter of Style (1976) — directed by Steve Soderberg featuring Shaun Tomson & others in California/Hawaii. Free Ride (1977) — directed by Bill Delaney, focusing on Australian surfers like Richards and Tomson in Hawaii & California. Fantasea (1977‑79) — directed by Greg Huglin, filmed in South Africa, Hawaii, Australia, California and featuring South Africans and Aussies in major wave zones. Storm Riders (1982) — while slightly later, directed by Jack McCoy & David Lourie, spans Africa, Hawaii, Australia and epitomises the global wave‑chase era following the mid‑70s breakthroughs.

These films together tell the story of how surfing shifted from local Hawaiian tradition into global athleticism and ambition. Bustin’ Down the Door serves as a documentary reflection of that era — the cultural clash, the surf innovation, and the foundations of modern professional surfing.

?? TASTY WAVES AND A COOL BUZZ: SURF COMEDIANS FAST TIMES AT RIDGEMONT HIGH (1982)

From Gidget (1959) to North Shore (1987) to Surf’s Up (2007), Hollywood has tried to capture the magic of surfing with mixed success. Real surfers like to explaim “Hollywood don’t surf!” but the truth is, these Hollywood “Waxploitation” movies have produced some classically funny characters: Frankie Avalon foreshadowed Austin Powers with his Potato Bug in Muscle Beach Party (1964), and Harvey Lembeck made ‘em laugh with bugsy biker Eric Von Zipper in Beach Party (1963) and its sequels. Sean Penn drew on his real surfing experience growing up in Malibu to nail his portrail of Jeff Spicoli in Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), and Gary Busey played Mick “the Masochist” in Big Wednesday (1978) as well as FBI Agent Angelo Pappas in Point Break (1991). John Philbin played Turtle in North Shore (1987), while Shia LaBeouf, Jeff Bridges, and Zooey Deschanel voiced the surfing penguins in Surf’s Up (2007). And who can forget Jack Kahuna Laguna from Sponge Bob Square Pants (voiced by Johnny Depp)?

And perhaps the most comic surfing character of all: Colonel Kilgore from Apocalypse Now.

GALERIE DES SURF CHARACTERS AMUSANTE CHRONOLOGIQUE

THE PRICE OF GAS: SURFER STUNTS IN HOLLYWOOD. POINT BREAK (1991)

This is the visualization of an article Ben Marcus wrote for The Surfer’s Journal in ??? it’s about surfers doing stunts in Hollywood movies - about surfing and not about surfing:

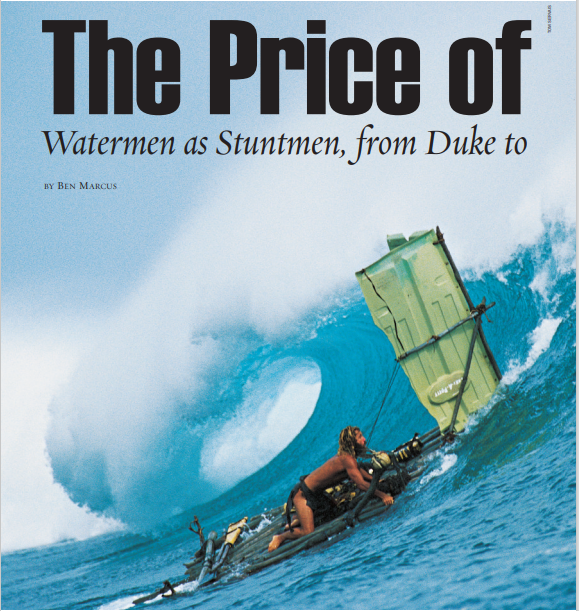

Darrick Doerner doubling for Patrick Swayze and deliberately wiping out at Waimea Bay doubling as Bells Beach for the 50 Year Storm at the end of Point Break was one of the most hair-raising, eardrum-busting stunts done by a surfer in a Waxploitation movie.

But there’s also the tragic irony of Todd Chesser blowing off the final stunt for In God’s Hands because he objected to the use of PWC in big surf, and going back to Oahu where he drowned at Outside Log Cabins. In a situation where a PWC might have saved him. Buzzy Kerbox did the stunt.

Noah Johnson doubled for Rochelle Ballard in the final Pipeline sequence for Blue Crush after Ballard was nearly paralyzed from a collision with Chris Won’s hard Hawaiian okole at Laniakea. Ballard was heartbroken to miss the opportunity to surf perfect Pipe with only one other person. Noah Johnson doubling for a girl surfer goes back to Mickey Munoz doubling for Gidget at Secos in the late 1950s.

Surfers have also done stunts and taken beatings in non-surfing movies: Gerry Lopez got hurt jumping onto a horse that bucked while doing his own stunts for the role of Subotai to Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Conan the Barbarian.

Jon Roseman did all of Tom Hanks’ water stunts for Castaway - nearly getting bent in a water tank doing the plane crash scene and teaming up with Don King to do spectacular raft-over-the-wave at Cloudbreak at the end.

Big wave surfer Brock Little proved he could fall in a spectacular wipeout at Waimea during the 1990 Eddie, then did stunts for Pearl Harbor and was surprised by how dangerous stunt work really was. Director Michael Bay and stunt coordinator Terry Leonard liked the cut of Brock’s job and that extended a solid stunt career for Brock, which included In God’s Hands (1998), Training Day (2001), Pearl Harbor (2001), Live Free or Die Hard (2007), Tropic Thunder (2008), Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (2009), and Transformers: Dark of the Moon (2011).

DON KING AND JEFF HORNBAKER: THE HOLE (1996), NO DESTINATION (1997/1998)

Because Don King worked as a water cinematographer on Second Unit for Castaway, Die Another Day, Blue Crush, Soul Surfer, Lords of Dogtown, Riding Giants, In God’s Hands, City of Angels, Lost and dozens of other Hollywood non-surfing and surfing movies, the stunts episode is a good segue to feature the work of Don King and Jeff Hornbaker - who are worth an episode for their work in and out of the surfing world.

According to Chat GPT: “Don King and Jeff Hornbaker co-directed the surf films The Hole (1996) and No Destination (1997/1998), creating cinematic journeys that blend epic waves, travel, and surf philosophy. Don King isn’t just a surf cinematographer — he’s a highly versatile camera artist whose work spans Hollywood features, documentaries, and television. Raised in Hawaiʻi, he honed his water-camera skills and athletic feel from swimming and water polo before applying them to major film productions.

In addition to surf movies, King has shot second-unit or water sequences for blockbusters — for example, he was the second-unit Director of Photography for Cast Away (2000), capturing ocean scenes and stunts.

He also worked on Die Another Day (2002), contributing as an additional unit photographer / director, notably during Bond’s water action sequences.

Beyond that, his credits include The Endless Summer II (1994), The Living Sea (1995), Blue Crush (2002), Riding Giants (2004), and even TV work like six seasons of Lost.”

Jeff Hornbaker, for his part, has been a prominent surf still-photographer and filmmaker since the 1970s. Together with King, he helped frame The Hole and No Destination with a unique eye for both the raw power of waves and the personal stories of surfers like Tom Carroll, Kelly Slater, Chris Malloy, Ross Clarke-Jones, Pat O’Connell, and others.

MODERNISM AND MOMENTUM: TAYLOR STEELE, JACK JOHNSON, THE BROTHERS MALLOY 1990s

The 1990s marked a renaissance and reinvention in surf filmmaking—a bridge between the raw, rebellious energy of the 1970s and 1980s and the polished, global aesthetic of the digital age. It was an era of experimentation, subculture, and personality, when surf films began blending cinematic craft, punk ethos, and emerging global surf exploration. The decade saw the rise of both independent auteurs and surf-industry-backed filmmakers who reshaped how surfing looked, sounded, and felt on screen.

Key auteurs included Taylor Steele, whose 1992 film Momentum revolutionized surf cinema with fast editing, punk soundtracks, and the rise of the “Momentum Generation” (Kelly Slater, Rob Machado, Shane Dorian, Kalani Robb, Taylor Knox). Steele followed it with Focus (1994), Good Times (1996), and Loose Change (1999)—all of which made surf films cool to mainstream youth again.

Meanwhile, Jack McCoy brought a cinematic eye and oceanic mysticism to the genre with Green Iguana (1992), Bunyip Dreaming (1994), and The Occumentary (1998), celebrating Aussie icons like Tom Carroll and Ross Clarke-Jones with lush cinematography and storytelling flair.

On the more avant-garde side, Thomas Campbell began developing his painterly, soulful aesthetic—later seen in The Seedling (1999)—ushering in the art film era of surf cinema that would dominate the early 2000s.

J Brother’s surf film Adrift was released in 1995 and focuses on the longboard revival, highlighting generations of surfers like Donald Takayama and Nat Young. Its style—emphasizing mood, aesthetics, and longboard culture—aligns closely with the contemplative, artful approach of Thomas Campbell’s surf films, though few other titles by J Brother are publicly documented.

In short, the 1990s was the “modernist decade” of surf film—when surfing on screen evolved from homegrown adventure reels into a global youth-culture art form, powered by music, motion, and myth.

?? THE SURFER MAGAZINE SURF VIDEO AWARDS AND JACK MCCOY (1996)

GOING PRO: 2004+

According to Chat GPT: “The first GoPro camera — the GoPro HERO 35mm — was released in 2004.

It was a simple 35mm film camera that mounted on a wrist strap, designed by Nick Woodman for capturing action sports like surfing. Digital GoPros came later, with the HERO Digital debuting in 2006, and the first HD model (HERO HD) launching in 2009, which truly revolutionized surf and action-sports cinematography.”

The introduction of the GoPro in 2004 marked a revolutionary turning point in surf filmmaking, effectively democratizing the art of capturing waves. Before GoPro, filming surfing required bulky 16 mm or digital cameras, water housings, and often a crew to follow surfers into the surf. This limited who could document surfing and the types of shots possible. With the GoPro’s small, lightweight, and waterproof design, any surfer could now carry a camera on their board, chest, or head, capturing immersive, first-person perspectives previously impossible.

This innovation didn’t just expand access—it changed the visual language of surf films. Surfers could document themselves and friends, create instant social media-ready content, and experiment with angles, slow-motion, and POV shots that emphasized the feeling of riding a wave rather than just its spectacle. In essence, the GoPro launched a new era: surfers became filmmakers, and the line between participant and documentarian blurred. Just as Super 8 did in the 1970s, the GoPro gave the sport its own eyes and its own narrative voice, forever altering how waves, tricks, and surf culture are experienced and shared.

GIRLS ON CURLS ON FILM: BLUE CRUSH (2002)

Blue Crush (2002): The Cultural Wave

The 2002 film Blue Crush, directed by John Stockwell and starring Kate Bosworth, Michelle Rodriguez, Sanoe Lake nad Keala Kennelly, marked a breakthrough moment for women’s surfing in mainstream cinema. Shot primarily on Oʻahu’s North Shore, it followed a group of young women working at a resort by day and chasing Pipeline barrels by dawn. It wasn’t just a surf film—it was a statement about ambition, fear, and female athleticism in a male-dominated lineup.

But Blue Crush didn’t come out of nowhere. The name itself was borrowed, with permission, from an earlier surf video by Bill Ballard, released in 1998, also titled Blue Crush. Ballard’s version was a documentary-style surf film showcasing some of the top women surfers of the late 1990s—Layne Beachley, Rochelle Ballard, Megan Abubo, and Kate Skarratt among others—charging heavy waves and proving that women’s surfing deserved equal respect and coverage. That project was groundbreaking within the surf community, though it reached a much smaller audience than the Hollywood film that followed.

TRAINING KATE

A Gallery of images showing John Philbin in Malibu and then Brock Little in Hawaii training Kate Bosworth

how to walk the walk, talk the talk, hold a surfboard, paddle and look like a real surfer.

When Universal Pictures chose the title Blue Crush for the 2002 movie (based on Susan Orlean’s Outside magazine story “Life’s Swell”), it symbolically built upon Ballard’s celebration of female surfers—translating that energy into a stylized, narrative format aimed at a wider public. For many young viewers, Blue Crush became a cultural touchstone, inspiring a generation of women to paddle out.

Episode Framing: “Blue Crush — Looking Back and Forward”

The Blue Crush episode of Surfing Through the Lens will use the film as both a pivot point and a mirror, looking backward and forward in time:

Looking Backward:

waikiki through the first half of the 20th Century, to Marilyn Monroe surfing tandem with Tommy Zahn in the 1940s and women surfers like Mary Ann Hawkins who paved the way for modern women surfer.The episode traces cinematic depictions of women surfing before 2002—from women surfing tandem and solo in the bubbly innocence of Gidget (1959) and the beach-party era of the 1960s, through the underground surf culture of the 1970s and 1980s, where women like Rell Sunn, Jericho Poppler, and Lynne Boyer carved out their own space on screen and in real life.

Looking Forward:

After Blue Crush, women surfers gained unprecedented visibility—both in documentaries and global media. The story can highlight how portrayals evolved through films like Step Into Liquid (2003), Beyond the Surface (2014), and Girls Can’t Surf (2021), and how new generations—Carissa Moore, Stephanie Gilmore, Bethany Hamilton, and Coco Ho—became cinematic subjects in their own right.

The goal: to show how Blue Crush served as a turning point where Hollywood spectacle met authentic surf progression, and how the representation of women surfers has moved from novelty to normality.

WOMEN ON WAVES THROUGH THE YEARS

SHOW THE RANGE OF IMAGES FROM WAIKIKI IN 1906

Robert Bonine’s “actuarial” film of Canoes, Waikiki in 1906 - the first moving images of surfing. Shuts down the thought that surfing was dead in Hawaii at the turn of the century.

Robert Bonine and his hand-cranked kinetograph.

Another Waikiki scene from Robert Bonine.